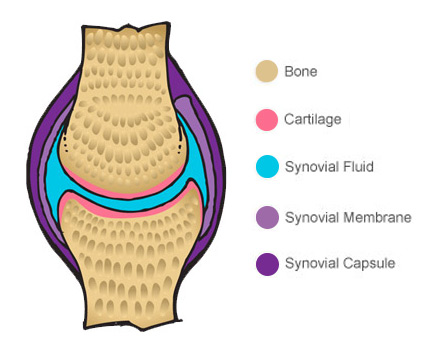

Inside a healthy joint, moving surfaces are covered by a layer of cartilage which stops two bone surfaces rubbing together and creating friction. Movement of the joint is made smoother still by the synovial fluid, which bathes the cartilage in lubricating molecules.

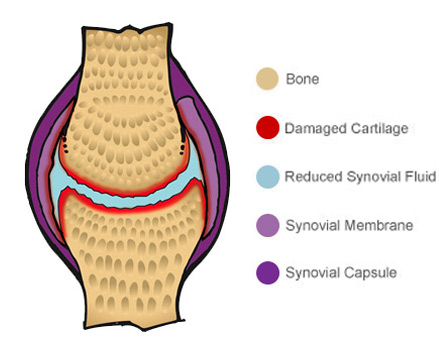

However with osteoarthritis, the integrity of the joint is compromised.

The cartilage begins to wear thin, sometimes getting worn away completely, while the level of lubricating molecules in the synovial fluid and on the cartilage become depleted.

The degradation inside osteoarthritic joints contributes to inflammation, joint stiffness, reduced mobility and pain upon movement. As the disease progresses, symptoms become more severe and debilitating, with pain sometimes becoming a permanent feature.

Essentially, there are two types of osteoarthritis – Primary or Secondary. The key difference between these two types is down to the underlying cause.

Primary osteoarthritis

This type of osteoarthritis is associated with aging, affecting people aged around 55+ and is the result of wear and tear on your joints. The more you age, the more likely you will be affected by osteoarthritis. The Joints most commonly affected are knees, hands, the spine, and hips.

Secondary osteoarthritis

This type of osteoarthritis is likely to affect people who are predisposed to the condition through various means such as obesity, genetics, the result of another disease or previous trauma such as fracture or ligament rupture.

There is no cure for osteoarthritis, but you can help relieve the symptoms by maintaining a healthy weight and regular exercise to keep active, build up muscle and retain joint mobility.

The type of painkiller (analgesic) your GP may recommend for you will depend on the severity of your pain and other conditions or health problems you have. The main medications used are described below.

If you have pain caused by osteoarthritis, your GP may suggest taking paracetamol to begin with. This is available over the counter in pharmacies without a prescription. It is best to take it regularly rather than waiting until your pain becomes unbearable. However, when taking paracetamol, always follow the dosage your GP recommends and do not exceed the maximum dose stated on the pack.

Despite its popularity, recent study evidence has questioned the usefulness of paracetamol in treating osteoarthritis. Evidence published in the Lancet lead to the conclusion, “we see no role for single-agent paracetamol for the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis irrespective of dose”. The reference for this is Lancet 2016 Mar 17. pii: S0140-6736(16)30002-2.

If paracetamol does not effectively control the pain of your osteoarthritis, your GP may prescribe a stronger painkiller. This may be a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). NSAIDs are painkillers that work by reducing inflammation. There are two types of NSAID and they work in slightly different ways:

Some NSAIDs are available as creams (topical NSAIDs) that you apply directly to the affected joints and can be available over the counter, without a prescription. Some oral NSAIDs are available without a prescription. As well as helping to ease pain, they can also help reduce any swelling in your joints. Your doctor will discuss with you the type of NSAID you should take and the benefits and risks associated with it.

NSAIDs carry numerous warnings and must be taken with caution. They may not be suitable for people with certain conditions, such as asthma, a peptic ulcer or angina, or if you have had a heart attack or stroke. If you are taking low-dose aspirin, ask your GP whether you should use an NSAID

Similarly NSAIDs can interfere with medications, for example negating the effect of most blood pressure medicines. You should always consult with your GP to see if NSAIDs are suitable for you.

Opioids, such as codeine, are another type of painkiller that may ease your pain if paracetamol or NSAIDs do not work. Opioids can help relieve severe pain, but can also cause side effects such as drowsiness, nausea and constipation.

Codeine is found in combination with paracetamol in common preparations such as co-codamol.

Other opioids that may be prescribed for osteoarthritis include tramadol (brand names include Zamadol and Zydol), and dihydrocodeine (brand name DF 118 Forte). Both come in tablet form and as an injection.

Tramadol is not suitable if you have uncontrolled epilepsy, and dihydrocodeine is not recommended for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

If you need to take an opioid regularly, your GP may prescribe a laxative to take alongside it to prevent constipation.

If you have osteoarthritis in your hands or knees and topical NSAIDs have not been effective in easing your pain, your GP may prescribe capsaicin cream.

Capsaicin cream works by blocking the nerves that send pain messages in the treated area. You may have to use it for a while before it has an effect. You should experience some pain relief within the first two weeks of using the cream, but it may take up to a month for the treatment to be fully effective.

Apply a pea-sized amount of capsaicin cream to your affected joints up to four times a day, but not more often than every four hours. Do not use capsaicin cream on broken or inflamed skin and always wash your hands after applying it.

Be careful not to get any capsaicin cream on delicate areas, such as your eyes, mouth, nose and genitals. Capsaicin is a molecule found in chilies that causes the burning sensation everyone is familiar with, so if you get it on sensitive areas of your body, it is likely to be very painful for a few hours.

You may notice a burning sensation on your skin after applying capsaicin cream. This is nothing to worry about, and the more you use it, the less it should happen. But avoid using too much cream or having a hot bath or shower before or after applying it, because it can make the burning sensation worse.

If your osteoarthritis is severe, treatment using painkillers may not be enough to control your pain.

In this case, you may be able to have a type of treatment where medicine is injected into the joints affected by osteoarthritis. This is known as intra-articular injection.

If you need intra-articular injections, it is likely that you will have injections of corticosteroid, a medicine that reduces swelling and pain.

If you get a prolonged response to the injection, it may be repeated. Ideally, you should have no more than three corticosteroid injections a year, with at least a three-month gap between injections.